PAULINA KOROBKIEWICZ

WALL UNIT

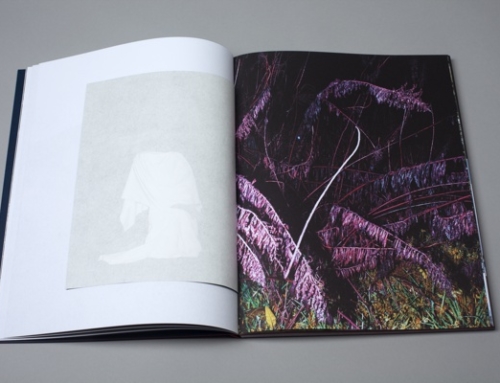

‘Wall Unit’ is a visual exploration of interior decorations and their sociohistorical roots. In the project, through the photos of furniture from the socialist era, individual decisions made inside of private spaces testify of the collective history of the nation. ‘Wall unit’ uses the material remains of the system as a tool for investigation of how socialism influenced contemporary taste and aesthetics in Poland and neighbouring Lithuania.

The tabloid format of ‘Wall Unit’ was inspired by newspapers from the socialist period and chosen deliberately to convey the impression that the work itself could have been a part of the interiors from that time.

WALL UNIT

The aesthetics of the Polish People’s Republic (1950s – late 80’s) was dictated by the underdevelopment of the economy and the existence of the Iron Curtain – the political and cultural boundary dividing Europe into two separate areas. It resulted in a shortage of common goods such as food, clothes and furniture. Empty shops were a norm. People used to spend most of their time queuing to do their everyday shopping. The supplies delivered to the shops were the only choice available.

The most iconic piece of furniture during that time was a full gloss wall unit called Meblościanka (‘wall of furniture’) in Polish. It covered the longest wall of the biggest room in a typical 1960s – 80’s flat. Usually, Meblościankas had lacquered doors to achieve the full gloss effect, very desired at the time. Alongside Meblościanka, there was a number of other distinct items dominant in Polish interiors: wood paneling on the walls of tight dark corridors, convertible sofas, folding coaches covered with motley upholstering and colorful lamp shades adorned with fringes or fake flowers.

Other decorative characteristics were fern plants in simple flowerpots on windowsills covered with thick, amply tucked white net curtains. Through covering the windows they overshadowed the interior, making the room gloomy.

One of the reasons for the lack of diversity in household and interior products was the monopolistic structure of the government enterprises that postulated for functional, rather than aesthetically pleasing manufacturing. The last issues they took into consideration while creating new products were their beauty and diversity. The lack of competition on the market resulted in items of dubious aesthetics. Iron rules of socialism entered even private houses. Through limiting the choices, the authorities imposed a homogenous styling of furniture. A visitor of a few households would be surprised with the similarity of their interiors. Deprived of inspiration and individuality, customers were forced to rely on the limited, repetitive goods hard won in local shops.

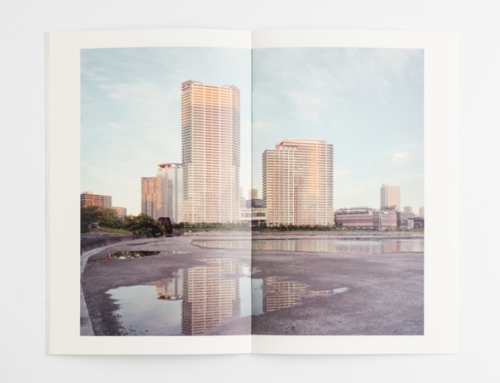

From the 1950’s onwards also public space started changing significantly. The key to this switch was World War II and the ensuing political system. Architecture’s task was to express national power and strength. Soviet architects favored monumentality. Architects and other makers of all socialist countries, where socialist realism also became the only approved method of artistic expression, followed them.

Growing up after the fall of communism, in the borderland of Poland and Lithuania, I observed constructions of that time and their similarity. School halls, consumers’ co-operative of local grocery stores ”PSS Społem”, restaurants with dancing areas, clubs, bus stations, offices and waiting rooms so large that it was difficult to fill them with furniture. Despite the passing of time, such locations can be easily found today. The system left its mark on the contemporary taste and aesthetics.

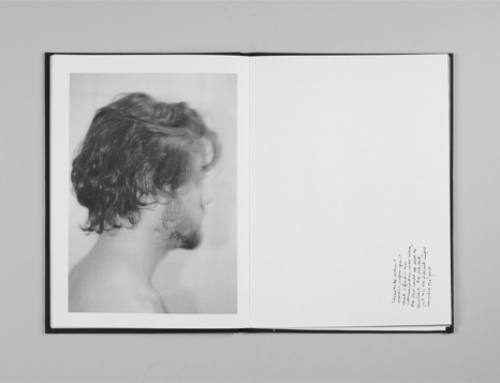

My choice of subject to photograph is personal and comes from observing my grandparents’ generation who often appreciated a uniformed lifestyle which was widely popular at the time: 7am – 3pm working hours, dinner in a work canteen, the 7 o’clock news on the only TV channel sitting in front of Meblościanka with centrally placed TV set “Belweder”- this was the pattern of life in the majority of households from that era.

Paulina Korobkiewicz (b. 1993) is a Polish photographer and visual artist based in London. Her practice explores public space and human interactions in the urban context. She is interested in how the political transition influenced contemporary landscape in Poland and neighbouring post-communist states. Her images draw inspiration from sculpture and architecture, and translate to a graphic conceptual style. Paulina graduated from Camberwell College of Arts in 2015. Her work has been the subject in exhibitions internationally and has been featured in a variety of publications. In 2016 she self-published the second edition of her first photobook Disco Polo. She was nominated for Magnum Photos Graduate Photographers Award 2017; shortlisted for Belfast Photo Festival Open Submission 2017, Bar Tur Photobook Award 2015 and selected for Creative Review & JCDecaux Talent Spotting Guide 2015. Her photobook Perspectives is the winner of Camberwell Book Prize 2016.