MICHAŁ SIAREK

ALEXANDER

‘Alexander’ is a story based on the relationship between politics, history and culture, centred around the construction of a national myth in the (Former Yugoslav) Republic of Macedonia – a state with no name, fixated on a dispute about origins so distant that they may have never existed at all.

You can see the ‘Alexander’ exhibition between 18 May and 8 June 2018 in FORT Institute of Photography in Warsaw. You can also join a talk and launch of the ‘Aleksander’ photobook as a part of a Krakow Photomonth festival. If you would like to simply order the publication, you can do it here.

One of three tall ships built in the bed of Vardar River to serve as restaurants and hotels

Skopje, 2015

A story based on the relationship between politics, history and culture, ‘Alexander’ is centred around the construction of a national myth in the (Former Yugoslav) Republic of Macedonia – a state with no name, fixated on a dispute about origins so distant that they may have never existed at all. The very first thing I saw in the capital city of Skopje was the construction site of a 25-meter tall figure of a warrior on horseback which – as I found out later – was the statue of Alexander the Great. Over two millennia after the intrepid conquest, his legacy still kindles the imagination in those who believe to be descendants of his blood.

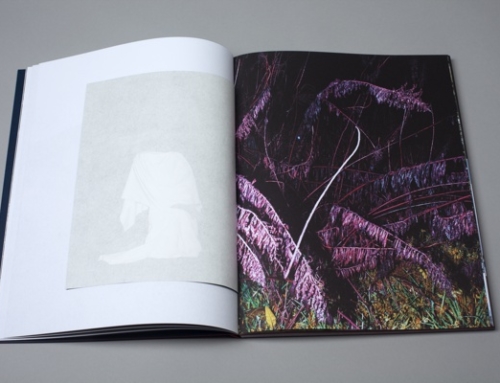

Marble excavated at the Mermeren quarry near Prilep is equal in quality to the famous Carrara marble. Despite many grand declarations, the marble was not widely used during the Skopje 2014 project. Its high cost meant that the stone was replaced with cheaper materials instead. The Greek-owned Mermeren quarry, however, can still list a few prestigious projects where its product has been used. Among them are The White City of Ashgabat, Turkmenistan, and the Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque in Abu Dhabi, UAE

Prilep, 2015

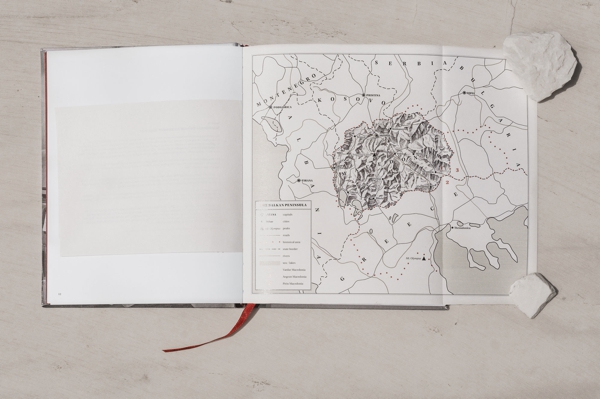

Established as one of the six socialist republics within the Yugoslav Federation, the modern state of Macedonia first surfaced in 1945, its name derived from one of the three geographical regions named Macedonia – surprisingly, though – not from the ancient kingdom. However, the term ‘Macedonian’ is the crux of the problem, as for generations, people were born Macedonians – identifying with their homeland, rather than with the state, within three countries, speaking numerous languages and defying easy understanding of their identity.

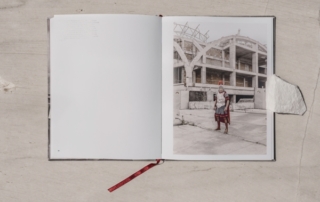

The construction site of the Archaeological Museum of Macedonia. The museum holds a copy of so-called “Alexander Sarcophagus”. The acquisition of the cenotaph sparked fierce public debate, as the object can’t be conclusively linked to Alexander the Great and there are multiple theories about its origin. The ruler’s final resting place was never disclosed after his remains disappeared from Egypt in 323 B.C. Despite its uncertain provenience, an exact copy of the artefact was installed in a dedicated chamber, crowning a collection of memorabilia that commemorates the alleged ancestor of modern day Macedonians

Skopje, 2013

Despite its peaceful secession from the war-torn Yugoslavia in the 90s, the newly proclaimed Republic of Macedonia immediately fell into a dispute with neighbouring Greece over the name and cultural heritage. The Greeks consider the legacy of Alexander the Great to be their cultural property. After nearly two decades of negotiations, the Macedonian Prime Minister announced in 2009 an architectural scheme titled “Skopje 2014”, marking yet another milestone. The equestrian figure in a rampant pose was the crown jewel of the new nation-branding policy, likening the modern day Macedonia to the ancient archetype of Alexander’s Kingdom.

A panorama of western Skopje as seen from the fortress hillside. The Scupi Roman military camp was originally located a few kilometres northwest of the modern day city centre, but after an earthquake in AD 518 the settlement was abandoned and a new stronghold was built by the riverside. The ancient remains of Scupi — complete with amphitheatre and aqueduct — are still close by, but remain abandoned and neglected

Skopje, 2014

A tremendous cultural shift, turning the state into a heritage theme park, was supposed to equip the Macedonians for the 21st century. Still, these make-believe stories ceased to convince the people after a political scandal exposed the cynicism of the rulers. Whereas today many see these stories as a forged decoy, others condemn their skepticism as treason, and choose to hold on to the myth, leaving the country divided and in chaos.

Boys from Nikola Vapcarov Folk Group before the annual performance

Skopje, 2015

Facing a dead end, the people of Macedonia revolted, which led to a peaceful, yet not seamless, transfer of power. With these events, my story – initially intended as a detailed gaze into a nation building process – seemed complete. However, Skopje baffled the world with yet another plot twist.

Popular club and restaurant “Roger Pijano”, located in the suburb of the capital

Skopje, 2015

The newly elected government decided to jettison the branding policy – in order to normalise the state’s relations with Greece – and agreed on removing some of the monuments. Although the restoration of the communist architecture – previously covered with neoclassical facades – seemed plausible, according to current plans, the fate of the unnamed “Warrior on the Horse” is also uncertain. And most probably, someone will some day bulldoze it as well, ultimately turning this political drama into a farce.

When I was working in Switzerland in the 90’s, I Iived together with Serbs, Bosnians, Croatians, Slovenians, let’s say people from all around the Federation. Whenever you’re distant from your homeland national pride and history become heated topics in discussions. Many of these people couldn’t accept the fact that we are an independent state. The centres of Yugoslavia were in Belgrade and Zagreb, but Skopje was a periphery. Most people barely know where my home country is, not to even mention our issues. Then, abroad, I made this tattoo of Philip II, father to Alexander the Great and to the Macedonian nation. […] I was born here, in Skopje, in the Republic of Macedonia. And nobody can take this pride away from me.

Boban, Manager

Excerpt from an interview conducted on the 24th of October 2016 in Skopje

Ironically, the name-game with Greece and the internal conflicts consolidated the soon-to- be-renamed Republic of Macedonia. Thus the state as we know it would not be there today, had it not been for the Alexander the Great confusion, which tightens even further the Gordian Knot of local complexity.

I eventually met numerous homegrown historians who spent hours with me, passionately drawing the link between the present and their long lost nobility. More than 2000 years after the empire’s collapse, we discussed origins so distant that they may have never existed at all. Yet generations of people in two different countries — and in multiple separate geographical areas — have already been born as Macedonians, making it a concept difficult to grasp. I bought a Serbian model set depicting Greek phalanx. The label stated it was Macedonian.

Szczecin, 2015

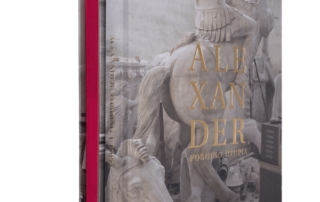

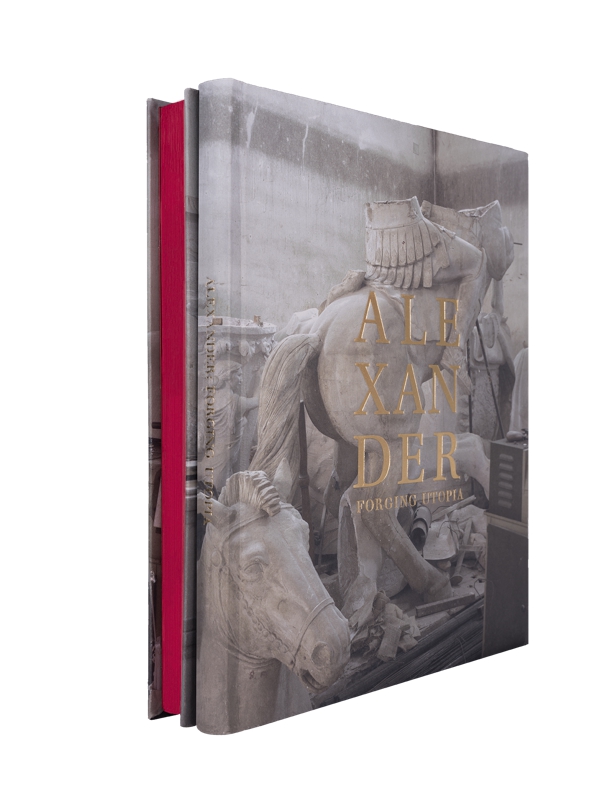

‘ALEXANDER’ PHOTOBOOK

144+20 pages, 43 plates, 207×263 mm,

offset print on Munken Lynx 150gsm,

hard cover, hand-coloured and waxed edges

Designed by Olga Łacna / IFF

Text authors: Marek Matyjanka, Michał Murawski

Project supported by Calvert 22 Foundation, FIDAL, Docking Station and Arctic Paper Polska

ISBN: 978-83-950913-0-8

Self-published in the edition of 750 copies, including 200 copies with limited cover (pre-orders and premiere only) and 30+3AP in portfolio edition (TBA).

My interests revolving around the nexus of geopolitics, history and national mythologies, I am adocumentary photographer of Polish origin with a special itch for cultural clashes of South-Eastern Europe. I am motivated chiefly by a drive to understand problems whose degree of complication fascinates me, thus I use photography as a means of observation and recording, in the same way that another person would draw a mind map to picture the problem. While photographing, I prefer to stay at a height, afar and with a technical camera, trying to take a “bigger picture”. The way of presenting my inquiries was meant to be credible, distanced and ambiguous. Still, instead of offering ready answers, my intention is to provide you the same information that I had myself, so that you draw your own connections and eventually come to a conclusion. In the period between 2010-18 (sic!) I studied towards an MA degree in photography at the Polish National Filmschool in Lodz, Poland. I graduated with “Alexander”, a story that I had pursued since 2013. If I were to make that choice again, I would have taken up Archaeology and Anthropology – the two toolkits that I am missing the most.