MARIUSZ BOGACKI

POLISH MUSLIMS

TATAR COMMUNITIES CELEBRATING THE END OF RAMADAN IN POLAND

Poland ranks among the most ethnically and religiously homogenous countries around the world – over 97% of Poles are white, Christian Catholic and speak Polish. Moreover, in recent years, there has been a notable rise in Polish nationalism and largely unfavorable views of immigrants – in particular of Islamic faith. Yet, for over 600 years a small minority group, known as Polish Tatars, has been practicing the Islamic religion successfully adapting to Polish values and customs.

Descendants of Mongol Empire, Tatars adopted Islam through the Ottoman Empire and later settled in the territories of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth around the 14th century. Inhabiting mainly the Northeastern regions of Poland, the Tatars have been living continuously in two villages given to them in exchange for their military service by Polish King Jan III Sobieski in 1679. While the great majority of the remaining 3000 or so Polish Tatars now live in larger cities such as Bialystok, Gdansk or Warszawa, the Bohoniki and Kruszyniany villages are home to the last two remaining Tatar Mosques in Poland which serve as the center of Tatar and Islamic culture and tradition.

Recent years saw a revival of Tatar culture by means of tourism and culinary trends. The increasing popularity of cultural tourism and the peaceful, picturesque landscapes of the region have been a drawing point for visitors from all over Poland and beyond. While the temples serve as an important center for information about Tatar culture and Islamic religion, local entrepreneurs promote their history and heritage by means of Tatar cuisine and ecotourism based largely on Tatar homestays.

The remaining few families of Tatar origin inhabiting the villages are not able to keep the Mosques open for daily religious services due to the dwindling numbers. The end of the holy month of Ramadan is one of the two main religious holidays (Bajram) that brings together the worshippers and people of Tatar origins from all over Poland, filling up the Mosques and invigorating the community.

Ramadan Bajram – the three-day celebration commemorating the end of the holy month of Ramadan – is the equivalent of Eid al-Fitr – the feast of breaking the fast – in the Arab world. Today the celebrations concentrate on the last day of Ramadan and include a communal morning prayer at the Mosque, visit to the Mizar (Tatar cemetery) and traditional dinners at one another’s houses.

Mr. Dzemil Gembicki works at the Kruszyniany Mosque as a tour guide and maintenance staff.

Over the centuries, Tatars have adopted to Polish customs, loosing their original language but staying faithful to their religion, traditions and cuisine. Commonly identifiable features of todays Tatars are their first names (influenced by the Arabic and Turkish cultures) and often-Asiatic facial features – homage to their Mongolian roots.

A boy and his father are on their way to the Kruszyniany Mosque during Ramadan Bajram.

Majority of Tatar men follow the traditional Polish dress code of wearing suits and/or shirts for cultural and official celebrations. Occasionally, specific fashion elements such as the tubeteika cap – originating from the Turkic ethnic groups of Central Asia – are observed.

Men are sat down before the main Morning Prayer commemorating the end of Ramadan. Kruszyniany Mosque.

In accordance with the Islamic faith, the prayers are conducted in Arabic. The sermon however is given in Polish. Two of the remaining Tatar Mosques are built in an architectural style similar to Catholic churches, but maintain the main guidelines of Islamic construction such as Mihrab (an indentation in the wall of the prayer room that marks the direction of the Qiblah – the direction which Muslims face during prayer), and the Minbar (a raised platform in the front area of a mosque prayer hall, from which sermons or speeches are given).

A girl is talking to her family member, before entering the Mosque. Kruszyniany.

Tatars adhere to the five pillars of Islam and teaching of Quran just as their fellow worshippers around the world. There are, however, differences resulting largely due to cultural assimilation and practicalities (i.e. dress code; ability to fulfill Salat – the daily prayers; a more relaxed attitude towards alcohol, greater gender equality).

Women are required to use a separate entrance to the Mosque and pray in a room separating them from men. Kruszyniany.

Recent years have seen an increased interest in Islamic teachings and culture among the youth. Young people are learning Arabic language and it is said that more and more abstain from drinking alcohol.

Sadoga – an exchange of sweets and food offerings, following the Morning Prayer of Ramadan Bajram. Kruszyniany.

Name of this ritual originates from a sweet dish made out of honey, flour and butter known in the Arab world as halva.

Imam Janusz Aleksandrowicz is walking to Kruszyniany’s Mizar (Muslim Cemetery).

Following the ceremony and upon a request, the Imam prays with each family over a grave of deceased family member. According to tradition, people cannot be buried in a gravesite once it has already been used, and therefore some of the oldest gravestones in the historic cemeteries date back to the beginning of 18th century. Tatars from all over Poland are buried at Mizaras in Bohoniki and Kruszyniany – two main and oldest Tatar cemeteries in Poland.

Mr. Adam Iljasiewicz at a family member grave at Bohoniki’s Mizar.

Prayers for the deceased are conducted on the right side of the grave, with the right hand placed on the gravestone. Mothers’ name of the buried family member has to be mentioned during the prayer – in case it is unknown, Eve, as the first mother, is mentioned. Tatar graves are decorated with flowers and the head of the deceased has to be facing Mecca.

Ms. Eugenia Radkiewicz gives a tour of a Mosque in Bohoniki.

Over the last decade, the Tatar tradition and pride has been reinvigorated, largely by ecotourism and interest in Tatar cuisine. To the mild dislike of some villagers, buses filled with tourists’ eager to learn about Islam and Tatar culture are almost a daily feature in both of the villages.

One of the many abandoned houses, built in a traditional northeast Poland architectural style – a wooden construction with a rooftop facing the main street. Kruszyaniany.

Farming industry – once the predominant occupation of Polish Tatars – is a dying livelihood. Young people in the villages are increasingly confronted with two choices: either abandon the family house in search of work in larger cities, or start an ecotourism or rural tourism business. The latter appears to be the only way of preserving the traditional way of countryside living, even if as some argue, an artificial endeavor.

Ms. Leijla Majewska – the owner of Leijla Guesthouse. Kruszyniany.

Historically Tatars were required to marry within their culture and religion. Nowadays most, but not all, of Tatars live in mixed-religious marriages and their children subscribe to the religion as agreed by their parents. A running joke in the Kruszyniany village is that the only problem with religious pluralism is the multitude of Holy Days preventing people from working.

The Annual Prayer for Peace and Justice in the World. Bohoniki.

As part of the end of Ramadan celebrations, representatives from all faiths inhabiting Bohoniki (Islamic, Christian Catholic and Christian Orthodox) meet for singing and dancing performances followed by joined prayer and meal.

Members of Bunczuk – traditional Tatar dance group – are waiting to perform during the Annual Prayer, next to the wooden Mosque of Bohoniki.

Architecture, food and religion are at the heart of Tatar culture today. The tradition has also been cultivated by the means of customary dress codes, dance groups and singers who perform regularly at local festivals and religious gatherings.

Selim Mucharski of the Bunczuk Dance Group dressed in traditional Tatar clothes.

Over the centuries Tatars abandoned their nomadic way of life and language, assimilating fully to the Polish society. However, tensions based on religious differences and ethnicity exists. While intensifying after the 9/11 attacks, conflicts remain an exception rather than a norm. “When asked whether we consider ourselves as Polish we always reply: ‘we don’t consider ourselves Polish – we are Polish’”.

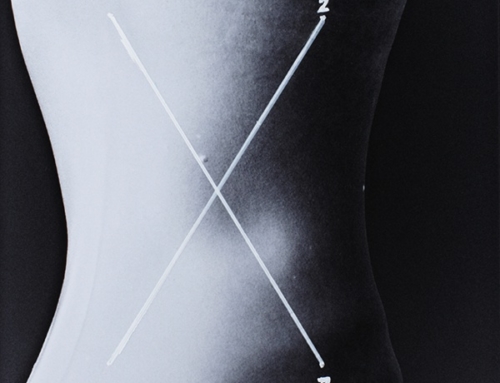

Islamic calendar is lunar-based, with the beginning and end of each month marked by the crescent moon. This crescent moon marks the end of the three-day Ramadan Bajram celebrations in Kruszyniany.

Drawing on an academic practice in anthropology and communication science, Mariusz Bogacki’s photography investigates contemporary notions of identity and culture in an increasingly globalised world. His work spans social documentary and photojournalism. He has worked internationally in Scotland, Palestine, India, China and Poland. His work has been published and exhibited at group and solo shows in cities such as Nanjing, Hong Kong, Rome, Edinburgh and recently has been shortlisted for the Royal Photography Society ‘International Photography Exhibition 160’ in London, UK.