CLOSE ENCOUNTERS #2

Milena Soporowska in conversation with Janek Jurczak

When you hear that war can be sometimes „boring” at first you feel confused or even offended. But war is not only spectacular explosions and “picturesque” violence – war is also waiting for the war to be over. Doing laundry, going for a walk or simply sitting in your room. Janek Jurczak, a young Polish photographer, went near the front line in East Ukraine to record the ordinary life in not so ordinary circumstances. Now he sells his photos to fund-raise money for a small community in Avdiivka, Donetsk suburbs, closely to Marjinka, where he had previously stayed and worked for a while as a paramedic (more info HERE).

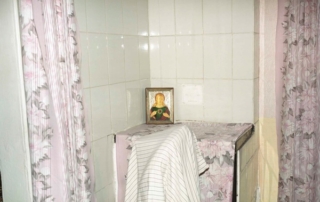

Sveta and Vitaly doing laundry after a day ofparamedic training organised by the Ukrainian Volunteer Army (UDA), Right Sector base, Donetsk Oblast, October 2017

UDA unit on the first front line in Marinka, Donetsk suburbs, November 2017

1. You came to East Ukraine as a medical assistant, but you’ve said that your organism “refused” to work in such manner. At the same time you’ve started your documentary project and carried it out even after you’ve stopped to participate as a paramedic. Why? Does photography makes it easier for you to cope with war reality? Does condensing it into an image, a story, makes you understand it more?

I went with my friend through a course for paramedics in Eastern Ukraine. I am not a doctor or a medical rescuer. I resigned naturally. It was just not for me.

My need to help resulted from necessity of getting involved socially. I want to create images, this need is deep inside of me.

At each stage of my work as a paramedic I made it clear that I am a photographer. I asked for permission to photograph every single time.

During New Year I’ve helped them to carry an old lady to a morgue. She died of an old age. I asked if I could go back for the camera and take a picture. I said it is important to document it. They agreed. I took a photo of a stretcher covered with a quilt. I did not take pictures of dead soldiers in the morgue. Few hours later a soldier who was transported to the hospital died of an exsanguination. I did not take a picture of him.

I chose not to make that kind of pictures. From my perspective, there is no point in producing images that we will not tame. Maybe we would tame corpse under a quilt. I don’t know, maybe.

A client of Irina’s in the makeup studio she opened in her room, Avdiivka, Donetsk suburbs, March 2018

Vladimir (right) outside a morgue, Avdiivka, Donetsk suburbs, January 2018

2. Most of your photos are made with the use of an intensive flashlight. This reminds me of a crime scene photography or classical reporter from the 50’s, with his enormously big flashlight as some kind of a reportage trademark. Pictures taken with the use of flashlight seem brutally even – you don’t get this chiaroscuro effect, everything is actually in the foreground. What effect and why You’ve wanted to achieve in this particular case?

In the beginning it was more of a need, not a conscious choice of aesthetics. I’ve worked on film-based camera and most of the rooms where deliberately darkened. It creates a completely different aesthetics used by Weegee, Arbus, Soth, Hornstra and so on.

I like it. Everything goes to one plan. It makes it more haramonized. More graphic.

I admire chiaroscuro in paintings and films. Though photography allows me to resign from it. It is I believe one of the things that distinguishes such aesthetics from a movie image.

Quoting Max Pinckers: The same world-problems that are caused by the West are re-consumed in the form of empathic imagery[…], cutting out the very victims themselves from the loop. Art though allows undermining reality, treating it as an object; it leaves space for self-reflection.

Of course flash is only a method to do so.

UDA (Ukrayinska Dobrovolcha Armiya) unit on the first front line in Marinka, Donetsk suburbs, November 2017

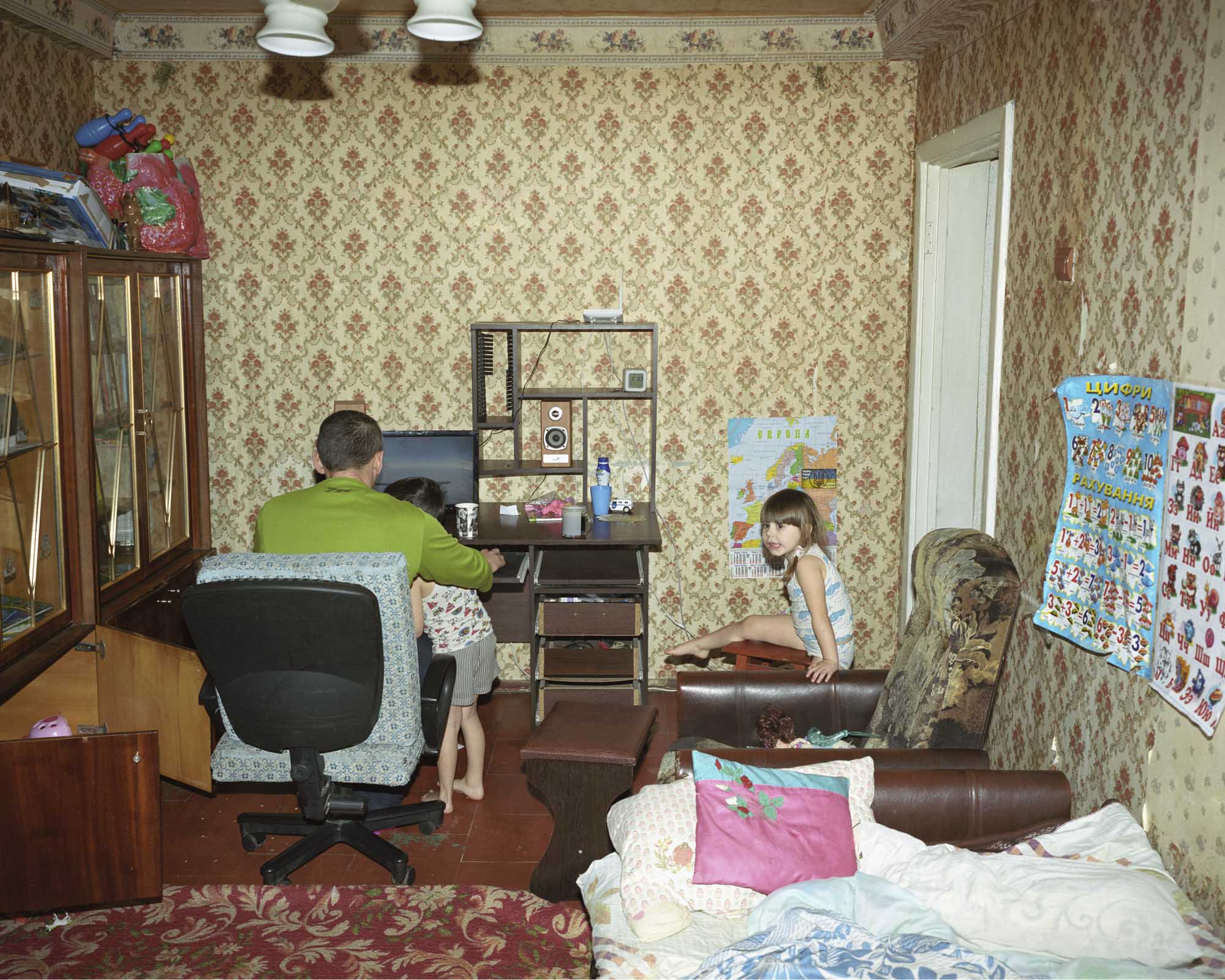

Andriej with his children, Avdiivka, Donetsk suburbs, December 2017

3. While photographing You came across a lot of different people who you’ve captured during intimate situations – for ex. hugging, being in a hospital or simply resting. Was it hard to convince them to be photographed? How do you build your relationship with your model? What was their attitude towards you as a photographer?

I wanted to be close to people. It allowed me to feel safe. I gave my privacy to those I’ve photographed, nothing more. In exchange, I got trust. We were together all the time. They accepted presence of the camera and took care of me. Only after time I’ve tried to give back what I received selflessly.

Most of my work was focused on documenting small communities living close to the front line. Coming back to the same people was important to me. I’ve tried above all to be with them as a human, not only as a photographer.

My intentions had to be clear from the beginning till the end. It was especially important while photographing soldiers. I had to face a very delicate situation – a published personal portrait could be used by the Russians. I had to ask repeatedly each time before I’ve used my camera.

Hospital, Avdiivka, Donetsk suburbs, March 2018

4. The world-famous photo of Robert Capa from 1936 showing Federico Borrell Garcia at the moment of death is probably the most brutal representative of a “decisive moment” conception and still functions as a model for reporters immersing into war reality. Most award-winning reportage photos represent this traditional “climax” approach. You instead choose to portrait people while doing laundry or participating in a breakdance class. What do you find fascinating about this mundane, ordinary activities?

I do not intend to see many wars. I prefer to think of myself as of somebody who does different things, including photographing in the conflict zone for a certain period of time. I try to show, using a photographic image, what war is for people I’ve met. I find war as everyday life, boredom, killing time and stress with rituals, routine. Only a small part of it is artillery fire and adrenaline. Most is waiting and adapting to the stress level, which is unhealthy to get used to.

After years of showing pictures of violence by the media, the viewer got accustomed to the sight of blood and such images stopped moving him. If something does not move us, we do not begin to tame it. If we do not tame it, then it is not ours and it does not concern us, we do not feel empathetic.

I find it important to inquire why something is happening, not what is happening. Quoting Rob Hornstra, It’s a way of looking at the world that does not require waiting for something to happen.

Blockhouse in Avdijivka, Donetsk suburbs, March 2018

Breakdance classes, blockhouse in Avdiivka, Donetsk suburbs, December 2018

5. You’ve been part of Sputnik photos mentorship program. Now you develop your career as a documentalist. Do you plan to stick with documentary photography as means of expression? If yes, why? If not, what do you find limiting in case of a document?

I am thinking about changing the medium into a movie image in the future, certainly not immediately. I try to be inspired not only by photography, I’m not closely attached to this particular medium. At the moment I am carrying out a new documentary project. I’ve changed the aesthetics, but not the method of work entirely. It requires a special type of loneliness – being lonely while being with people. The problem with documentary is that if You want to touch the essence of things, You often can not photograph it – such situations are too intimate, important for our protagonists, just like death or love. I do not know how much more I want to work in this way. Certainly I want to create images, most likely socially involved.

BUY PHOTOGRAPHS AND HELP COMMUNITY BY THE WAR ZONE IN UKRAINE: zrzutka.pl/peace-and-love

Heaters bought from funds collected during ongoing initiative photographed by Elena Pisareva

Tanja and Kristina with heaters (bought from funds collected during ongoing initiative) photographed by Elena Pisareva

Jan Jurczak (1996) – documentary photographer focused on social issues. Jan concentrates on intimate stories and tries to create a bond between photographer and protagonist. He finished Sputnik Photos Mentorship Program in 2018.

Milena Natalia Soporowska (Warsaw, Poland) – studied History of Art [main faculty] at College of Inter-area Individual Humanistic and Social Studies at University of Warsaw and Photography at The Society of Polish Art Photographers [graduated with distinction] and Academy of Photography. Currently studying Museology. Laureate of the 5th edition of ShowOFF contest for young talents at XI Krakow Photomonth [project: ‘Guest Rooms’, curator: Bownik]. Curator and co-organizer of several group exhibitions. Interested in spiritism and psychoanalysis. Writer and techno promoter.

Close Encounters is a series of interviews by Milena Soporowska with Polish photographers, conducted for Fresh From Poland – each consisting of 5 questions about just one specific project. ‘Close Encounters’, since Milena Soporowska is a sci-fi fan, derives from a movie title ‘Close Encounters of the Third Kind’ about aliens coming to Earth. Well, is every meeting with a human being not a meeting with a potential alien creature in a way? The purpose of these ‘close encounters’ is to know more about humans while studying their products – which are, in this case, photographs.